Geopolitics for the Security Professional

How many times has this happened during an intelligence briefing? The analyst puts up a slide or distributes a report with utterly banal statements. They are accurate but ultimately meaningless for the security professionals consuming the information. Examples:

China could invade Taiwan by 2030.

Nationalist movements are helping to break apart international institutions.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has destabilized the region.

The softening of relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia is an important development.

Regulatory environments prevent faster development of internet infrastructure.

Let’s be honest. Most security professionals get exasperated with the geopolitical reports they receive from either their in-house team or outside vendors because these reports often just summarize whatever is occurring in the news and are proffered without forecasting events or actionable analysis. This is why geopolitical risk analysis, especially within the context of strategic intelligence, is castigated by most security professionals and not a regular part of intelligence work. I will discuss in the future the importance of the actionability of intelligence, but here we will start with the importance of geopolitics. Hopefully, this will help security professionals recognize why it matters and analysts produce better reporting.

Why Geopolitics Matters

Geopolitics is the foundational issue for all of business and security. That might sound like a grand statement, but the facts stand for themselves. Security professionals would be doing a disservice to their clients to ignore such a potent force in world affairs.

When Professor John Mearsheimer, the preeminent neorealist, discussed in his book why his theory focused on great powers, he wrote that great powers have “the largest impact on what happens in international politics. The fortunes of all states—great powers and smaller powers alike—are determined primarily by the decisions and actions of those with the greatest capability” (Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (3rd ed.), p. 5). Although Mearsheimer is right when this deals with international politics, the choices by great powers impact everything from cybersecurity to domestic politics to capital markets to travel risks to regional stability to physical safety.

Consider the highly contentious issue of China claiming sovereignty over Taiwan and the possibility of invasion. This would not only likely lead to a major regional war, but the entire global economy would be devastated. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) makes practically all of the advanced AI chips multinational technology companies use to maintain their research and competitive advantage, including Nvidia, Google, AMD, Amazon, Microsoft, Cerebras, SambaNova, and Untether. Imagine the absolute chaos that would ensue if China invaded Taiwan. No country's economy would walk away unharmed.

Or look at how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has impacted food and gas prices along with other critical sectors like neon gas necessary for lasers in fabrication of semiconductors. All the way back in 2015, the Syrian migration crisis in Europe altered many domestic political arrangements on the continent. Right-wing populists gained a much stronger foothold on the continent because of the crisis, and the EU is precariously trying to keep a united institution despite pushback from right-wing politicians in France, Italy, and Hungary. The crisis occurred *partially* as a long-term consequence of the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 (i.e., the destabilization of Iraq, rise of ISIS, and the terrorist group’s contribution to the Syrian civil war following the Arab Spring).

All of these examples show how geopolitics has significant impacts on global economics, security, and politics. Security professionals would most assuredly be wise to pay attention.

Understanding Geopolitics

What is geopolitics? Geopolitics is the competition over geographical areas that are strategically important, the use of those geographical areas to achieve political advantages, and the interaction between geography, economics, and demography on political actors. Put simply, geopolitics is how political actors (states and non-states) deal with the people, resources, and territories surrounding their geographical areas of interest. Because the ability to project power across large areas is central to geopolitics, there is a reason the subject was developed after humanity gained the capability to traverse continents.

Importantly, geopolitics is not international relations, foreign policy, or national security. All four of these are interconnected, but they are distinct categories. Conflating them leads to poor analytic judgement and distraction from the critical issues. International relations is how all states interact with each other; foreign policy is the decisions by one state in how it deals with outside powers and groups; national security is the defense of the country from threats.

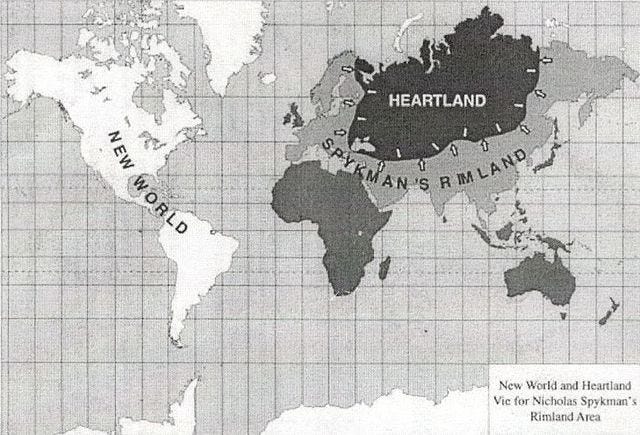

To better comprehend how all of this plays out, it is beneficial to start with the intellectual development of the subject. The three great theorists of geopolitics were Alfred Thayer Mahan, Halford Mackinder, and Nicholas Spykman, and they had essentially different approaches to the subject. Mahan (1840–1914) began geopolitical debates with his magisterial work The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783. Focusing on the rise of the British Empire, Mahan argued that controlling sea routes was the key to hegemony because maritime trade and colonies could best be controlled through this. On the other hand, Mackinder (1861–1947) developed the heartland theory when he delivered his paper "The Geographical Pivot of History" in 1904. The heartland theory was based on controlling land power in the interior of Eurasia, which was now imminently accessible by railroad. According to Mackinder, any state that controlled the heartland of Eurasia would be able to dominate the world. Finally, Spykman (1893–1943) offered a contrast to both of the previous theorists. Spykman’s argument was that to control the world one needed to control the “rimland” of Eurasia, which would give a country the ability to dominate the heartland.

Notice how each of the theorists connected geography to power politics. That is geopolitics. Now, an analyst does not necessarily need to be intimately acquainted with these theorists or accept their arguments to work on geopolitical issues. What is important is that analysts and security professionals understand the concept of geopolitics in order to do their work more effectively.

Analyzing Geopolitics

Like with every sub-field in security, geopolitical analysis requires serious study and training, and the average intelligence analyst has not had a sufficient education in the subject to analyze trends, forecast scenarios, and offer actionable insights. That’s a critical reason so many security professionals are frustrated when they receive geopolitical reports. Here I would like to discuss a framework for issue deconstruction to help analysts proffer better reports and assist other security professionals to interpret the reports.

The following are the topics and variables with which analysts should engage to forecast geopolitical events AND determine their impacts to business and security more accurately. Security professionals reading such reports should take note that these variables are addressed and ask questions on them if they are not.

Geography and power projection capabilities. Geopolitics by definition starts with geography. Analysts need to understand the location and topography of the country, but they also must understand how geography relates to power projection capabilities. I.e., does the country have a mountainous region, and can they scale those mountains? Are they landlocked? Do they have warm water ports? What's the size of their navy? All of these questions and more come together to understand the layout of the country and how the government is able to adapt to or overcome that geography.

Leadership personalities, ideologies, and perceived interests. Leadership matters, especially that leader's ideological framework and what they perceive to be their interests. One of the critical mistakes analysts made in arguing Putin would not invade Ukraine was that they grossly misunderstood his belief system. Xi, Trump, Biden, Macron, Modi, etc. all have different worldviews that determines their actions. Geopolitical analysis must incorporate assessments of the leader and take on their mindset because perception of issues and mindsets are quintessential to forecast behavior.

Political structures for decision making. A false assumption in modern international relations scholarship is the "unitary actor" that treats states as a single entity. Take the US as an example. The White House, executive bureaucracy, and Congress could all have different objectives, and the structure of decision making allows each to have an input or possibly stop the others. China, Russia, UK, Israel, etc. each have their own unique structures for decision making, and each institution or group within a government that has power might approach geopolitics differently.

Culture and identity. Despite the many attempts to lambast and demonize Samuel Huntington for his thesis in Clash of Civilizations, the truth is he was practically right. The culture and identity of a country, nation, or nation-state will absolutely impact their approaches to geopolitics. From pan-Arabism and pan-Slavism to the "One China" principle to the EU's cosmopolitanism, the broad culture and identity matters for geopolitical analysis. The best historical example, though, is the Bangladesh War of Independence in which cultural suppression by West Pakistan acted as a catalyst for nationalist sentiments.

Demographics. Demography plays a central role in geopolitics. Human geography, not just physical geography, deeply matters for state decision making and geopolitical analysis. Is the population aging? Are the educated young overly represented? Is there a rural/urban divide? What is the purchasing power and average income? Human factors must be acknowledged.

National resources, industrial base, and economics. The crux of how geopolitics impacts clients will be based on resources and industry. Will an invasion disrupt a supply chain? Will it cut off access to oil? What technology is produced in the country/region? Will a country's financial markets be destabilized? To answer these kinds of questions, analysts must first understand the resources, industry, and general economics of the country being assessed and how the region is impacted.

Surrounding countries. Finally, analysts should use the previously discussed variables for the countries surrounding the country or region in question. This is relevant for two reasons: opposing or allying countries will make similar decisions based on those variables, and to determine the risks to one's client the analyst needs to know how a decision will possibly disrupt the economy, people, supply chains, transportation, etc. elsewhere.

All of this may seem simple enough, but it is shocking how often intelligence teams fail to follow this type of framework, leading many security professionals to dismiss the utility of geopolitical risk analysis.

Successfully doing geopolitical risk analysis will take practice and study, but this introduction will hopefully help security professionals, especially intelligence analysts, move in that direction.