Understanding Russia: Insecurity and Authority

Grasping the historical ideology that underpins Russian foreign policy

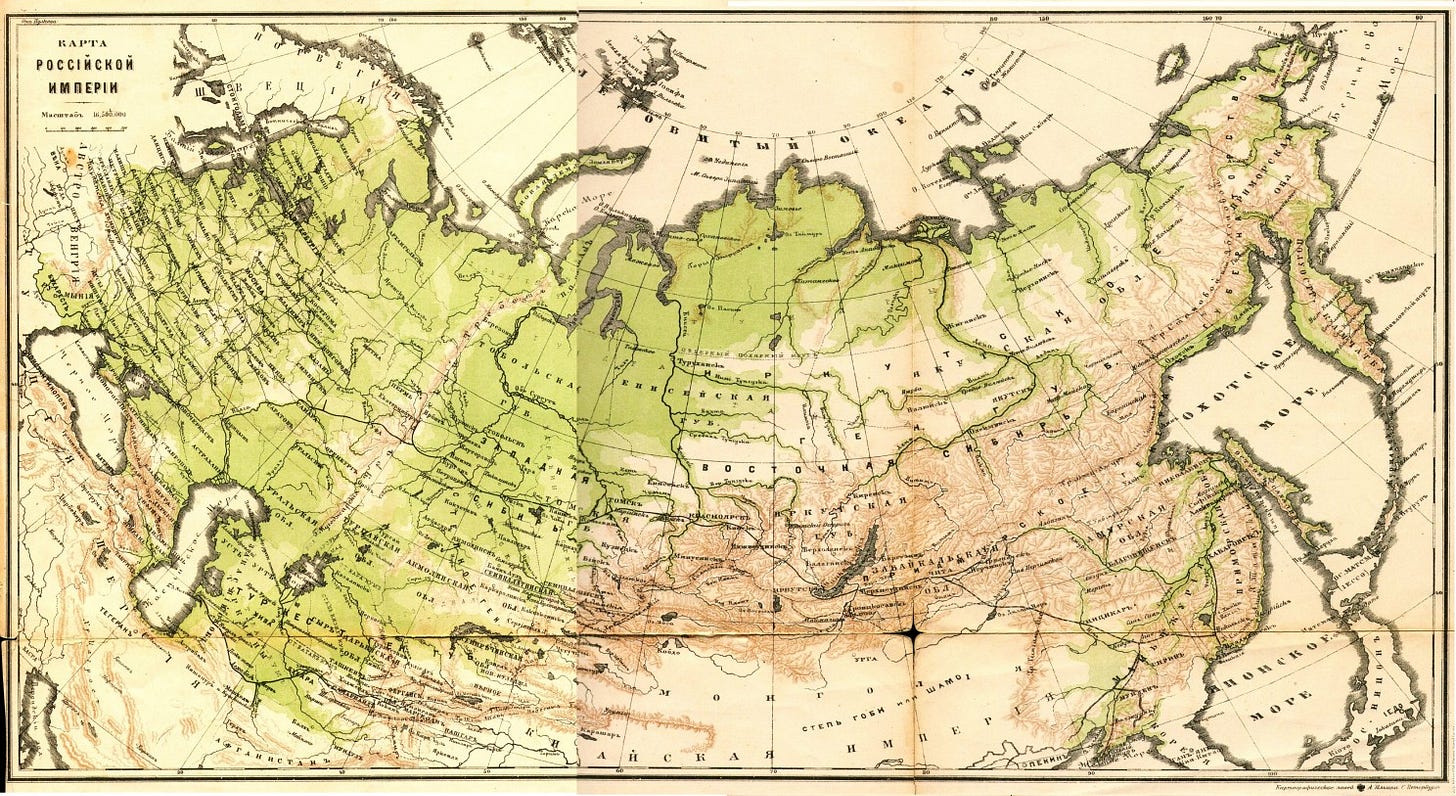

Russia remains a persistent threat to the international order and has a tremendous impact on geopolitical events across the world. Understanding Russian foreign policy is essential to forecasting geopolitical risks, but the lack of understanding has consistently led analysts to make false conclusions about Russian behavior over the past twenty years. Although Sir Winston Churchill famously described Russia as "a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma," the nature of the country is easily comprehensible from its history. Russia is a deeply insecure country because of its geopolitical position, diverse demography, and internal divisions, which has led them to believe in the fundamental importance of a strong, authoritarian leader capable of managing the anarchy of the world. That basis also informs their foreign policy where Russia focuses on territorial expansion to increase security and destabilizing possible competitors through any means necessary.

Russia’s oscillations and tribulations between the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 through the collapse of the Soviet Union to the resurgence of Russian power have never changed the fundamental characteristics of the country. Their national characteristics are rooted in a strongly hierarchical society based on a pessimistic view of human nature and existence, inevitably leading to czarism. For much of Russia’s history this was based on the theological underpinnings of the Orthodox Church, and during the Soviet Union the hierarchy was based on Marxist-Leninism embodied in the totalitarian nightmare of Stalin’s regime. Czarism is an authoritarian view of leadership in which legitimacy stems not only from the ruling ideology but also the leader’s status as a strong ruler pushing the territory and maximizing Russian greatness and power. That is why Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, and Stalin are all still ranked as Russia’s greatest historical rulers. Vladimir Putin’s regime exemplifies this tradition, and his understanding of Russia in the world is deeply influenced by this czarism.

[Note: Relatedly, one can also observe this worldview in much of Russian literature, such as Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment.]

Russian History: Peter and Catherine

Peter I (the Great) was czar and emperor of Russia from 1682-1725, and his reign was consumed with wars against their near competitors: the Swedes, Ottomans, and Persians. Despite the costs of these wars, Russia was able to expand its empire and turn the country into a naval power. In addition, Peter radically altered the country by introducing the Western Enlightenment and attempting to break some of the power of the hyper traditionalist Orthodox Church. Funnily, Peter also created the All-Joking, All-Drunken Synod of Fools and Jesters that mocked the Orthodox Church and engaged in licentious revelry. Although the Soviets castigated the institution of the czar, even Stalin admired Peter. In 1928, he wrote that "when Peter the Great, who had to deal with more developed countries in the West, feverishly built works in factories for supplying the army and strengthening the country's defenses, this was an original attempt to leap out of the framework of backwardness." Essentially, the Russians view strength of leadership as paramount for greatness.

[Note: I recommend reading Lindsey Hughes’ Russia in the Age of Peter the Great if you’re interested in this period.]

This is why Catherine the Great, a German-born empress who ruled from 1762-1796, remains one of the most popular historical leaders. Like Peter, Catherine greatly expanded Russian power and influence, taking control of the Crimean Khanate after defeating the Ottomans and then incorporating the Black and Azov Seas. In addition, Catherine led the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and colonized Alaska. Catherine’s enlightened despotism further modernized Russia by constructing many new cities, and she had the nobles build mansions in her preferred architecture. Similar to Peter, Catherine’s Enlightenment beliefs had her challenge the Orthodox Church, and she closed hundreds of monasteries, taking their lands for state purposes. Like many women monarchs of the early modern period, Catherine was able to dominate politics by appealing to a “masculine nature,” that is the same kind of strong leadership Peter showed. That is why she remains an institutional figure exemplifying the Russian view of government.

[Side note: I love the show The Great, but please do not reference it as even having a semblance of historical accuracy about Catherine…]

Underlying Ideology: Kennan and Dugin

George Kennan, probably the greatest observer of Russian/Soviet affairs, described in his famous “Long Telegram” in 1946 the essential nature of the Russian/Soviet character that would hold even in the post-Soviet world. Kennan was stationed in the Soviet Union during World War II, and he was devoted to studying Russian history, literature, and politics. In the telegram, Kennan noted, “At bottom of Kremlin's neurotic view of world affairs is traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity…And they have learned to seek security only in patient but deadly struggle for total destruction of rival power, never in compacts and compromises with it.” Insecurity about the world, both internal chaos and external threats, led Russians to support those strong leaders. In a later article in 1951, Kennan wrote, “No ruling group likes to admit that it can govern its people only by regarding and treating them as criminals. For this reason there is always a tendency to justify internal oppression by pointing to the menacing iniquity of the outside world.” Observe the language choices by Kennan. He is speaking to that insecurity and need for control that Russia leaders pursue and that informs their foreign policy decisions. One can also see this approach through the Okhrana (internal intelligence) and how the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia used similar counter-intelligence agencies.

[Note: Though I could never deny Kennan’s perspicacity about Russia, I fundamentally would have disagreed with him while alive about a number of issues. His pacific realism and impotent containment would never work, but that does not mean he was not insightful. However, if you’re interested in understanding him then I recommend reading Nicholas Thompson’s The Hawk and the Dove and John Lukacs’ George Kennan: A Study of Character.]

In modern Russia, Aleksandr Dugin became the go-to philosopher for expounding the latest iteration of this worldview. Dugin wrote The Fourth Political Theory in 2009, and the book became the intellectual justification for Putin’s rule. The Fourth Political Theory rejects liberalism, Marxism, and fascism, but then it takes from each of them to form a “timeless, non-modern theory” concerning Dasein (existence). Notice the use of that particular term. Dasein is the term German philosopher Martin Heidegger used in his text Being and Time (1927), and his understanding of existence is easily grafted onto the Russian pessimistic view. Then there is his understanding of geopolitics. According to Dugin, Russia must pursue a new Eurasian empire to counter the United States and Atlanticism because the West is a security and cultural threat to Russia. As he wrote in his 1997 book The Foundations of Geopolitics, “The new Eurasian empire will be constructed on the fundamental principle of the common enemy: the rejection of Atlanticism, strategic control of the USA, and the refusal to allow liberal values to dominate us.” The importance of Dugin for explaining the neo-czarist justifications of Putin’s actions is why Ukraine attempted to neutralize him (though they accidentally killed his daughter instead).

Contemporary Issues

One can easily see the application of Russia’s worldview to their foreign policy. Start little more than a decade ago when Putin began using Russian power to expand its territory slowly and attempting to destabilize its neighbors. There was the cyberattacks against Estonia in 2007, invasion of Georgia in 2008, the initial theft of Crimea in 2014, support of Assad’s Syria in 2015-present, and intervention in the Central African Republic (2018-present) and Mali (2021-present). Then there are the smaller or non-kinetic attacks, like disinformation and election interference from the United States to Moldova.

The current illegal invasion and conflict by Russia in Ukraine is best explained by applying this paradigm to Putin’s decision making. As Dugin put it in a speech, “So, the war is of multipolar world order against unipolar world order. It’s nothing either about Russia, Ukraine, or Europe; it’s not against the West and the rest; it’s humanity against hegemony.” Of course, Kennan foresaw this almost eighty years ago because he knew Russian history. In 1948, Kennan noted in a policy paper that Russia would never allow Ukraine to be independent because it was so central to Russian identity and worldview. Just think of the justifications Russia offered for the illegal invasion: halt NATO expansion, challenging the West’s desire for “infinite power,” protecting the ethnically Rus people in Donbas, and to “de-Nazify” Ukraine. Analysts can easily see how each of the justifications relate to the nature of Russian governing identity. Expand territory (Donbas and Crimea) to increase security, create chaos in the competition to limit their threats (NATO expansion and challenging Western power), and “de-Nazifying” Ukraine (stop any possible internal threats).

There are of course many aspects to Russian history and identity, but what is described above gives the essential characteristics of the country and explains Putin’s behavior domestically and internationally. Analysts and security professionals must keep this worldview in mind when assessing Russian behavior because it will most assuredly continue to influence Putin’s decision making (and whoever succeeds him).

I acknowledge your perspective; however, it appears to reflect false narratives originating from Moscow over the past five to six decades, mostly tailored for Western intellectual audiences.

The notion that Russia's expansion stems from geopolitical or demographic insecurities is a constructed narrative. Since 1945, the upper echelons of Russian elites have perceived external threats as significant, let alone. While there was some apprehension in 1991, it did not equate to a sense of insecurity.

Regarding the general populace, suggesting that ordinary Russians feel insecure is a misinterpretation. Historically, they have been deprived of agency and subjecthood. The Russian elite seldom sought the opinions of regular citizens, notably only in March 1917 and 1990. Many Russians inherently understand that their primary adversaries are domestic entities: the police, the ruling class, and the FSB.

Russia is Moscow's centralized totalitarian empire and a thermonuclear superpower. It does not exhibit an instinct of insecurity or fear of the external world. Moscow knows perfectly that the West is no threat for Russia. Moscow's invasions of other nations are driven by expansionist objectives rather, nothing related to defensive anxieties.

It's expansionism. Russia expands because an empire expands to the extent when it hits another empire. That's all it is. A 19th-century citation, despite its negative connotation of the author, encapsulates this sentiment:

> "I ask you, what has changed? Has the danger from the Russia side been lessoned? No. Rather, the delusion of the ruling classes of Europe has reached its pinnacle. Above all, nothing has changed in Russia's policy, as her official historian Karamsin admits. Her methods, her tactics, her maneuvers may change, but the pole star -- world domination -- is immutable. Only a crafty government, ruling over a mass of barbarians, could devise such a plan nowadays. Pozzo di Borgo, the greatest Russian diplomat of modern times, wrote to Alexander I during the Congress of Vienna that Poland was the most important instrument in carrying out Russian intentions for world domination; but it is also an insurmountable obstacle, if the Pole, tired of its unceasing betrayal by Europe, does not become a fearful whip in the hands of the Muscovites. Now, without speaking of the mood of the Polish people, I ask: Has anything taken place that would frustrate Russia's plans or paralyze her actions?"

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867/01/22.htm

Peter Zeihan concurs with you and repeats the same misconception. A common tendency among Western intellectuals is to overlook the fact that since 1941, the only global power that has posed a real threat to Russia is China. This was evident in 1969 when the Chinese military attacked Russia, and it continues today with the Chinese government issuing statements and papers asserting territorial claims over Russia’s Far East.

Your understanding of Russia’s intentions and motives is as flawed as your perception of Alexander Dugin’s role in Russian politics. Dugin is not "Putin’s brain"—in reality, Putin has little regard for Dugin’s thinkings and would likely be indifferent if Dugin were eliminated. Dugin is not a philosopher or an leader of Russian ideas, but rather a propaganda figure, much like Dmitri Trenin (Дмитрий Тренин), Dmitri Simes (Дмитрий Константинович Симес), Vladimir Posner (Познер), and Metropolitan Hilarion (Григо́рий Вале́риевич Алфе́ев). Moreover, compared to Dugin, Trenin, Simes, and Hilarion have far greater intellectual standing and significance. It’s worth noting that Dugin’s spoken Russian is worse than Steve Bannon’s spoken English. His only real distinction in Russia is being the son of a KGB general.

Yes: the "Long Telegram" contains perhaps George Kennan’s greatest misjudgment, to the extent that one might question his competence and even scrutinise his time in the USSR more critically.

Vlad Vexler comes closer to reality when he says, "Regime security is the reason for Russia’s wars," but even this framing is misleading. The simplest way to describe Russia’s motivation is: "I invade because I can."

Yes, if only we still had “security and expert analysts